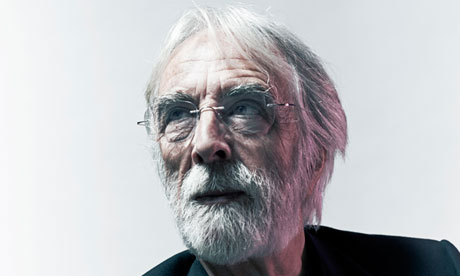

On the eve of the release of his eleventh film, the Palme d’Or winning Amour, a seventy-year old Michael Haneke is now placed firmly amidst the dazzling heights of European cinema greatness. Amour centers on the failing bond of love between an elderly couple when one of them suffers a stroke, so it would appear that Haneke hasn’t stepped too far out of his comfort zone – but when his mastery at making even scenes of intense malaise so intermittently watchable it’s easy to be captivated by the genuine malice found in every frame. The lack of soundtrack, long and seemingly pointless takes and low-key magnetic performances blend to produce a hyper-realist aesthetic that augments the intensity of the extremist stories he tells. While compulsively watchable, his work is often deeply unsettling and hard to stomach, in the best possible way of course. Let’s have a look at some particularly unpleasant examples.

The Seventh Continent

Haneke’s ambitious debut, and a showcase for his emerging style, The Seventh Continent concerns a real-life case of family suicide. Employing a sparse narrative approach, the film provides us with almost no explanation for the family’s decision to end their lives- a staple of Haneke’s filmmaking. Not everything in life happens for a reason and his oeuvre is reflective of that. He uses everyday routine practices to highlight the cyclic monotonous existence of a suburban family, but the opening car wash scene creates a sense of claustrophobia perfectly. It’s just another wasted moment and is highly symbolic of their passage through life. The car creeps along; an empty vessel beyond their control.

Funny Games

Haneke’s self-referential and fourth wall breaking masterpiece, Funny Games might be said to manipulate audience expectation somewhat. A wealthy family move to their scenic summer home where they are randomly taken hostage and brutally tortured by a pair of sadistic young men- one of whom occasionally turning to address the audience, implicating us in their callous actions. In one scene, the wife manages to grab a gun and shoot one of her torturers, before his accomplice simply rewinds the scene, this time getting to the gun before her and punishing her for resisting. Deliberately frustrating and a credit to Haneke, the scene works because of our empathy for the victims. He shows us the ‘movie’ scenario, because this is what we want to see, only to snatch it away and leave us with the cruel reality of it all. No happy endings, please.

-> Benny’s Video

Benny’s Video

Haneke’s second feature is a disturbing examination of an unhinged teenager who perceives his life as distilled through video images. Before the opening credits have even appeared, we are subjected to footage of a pig being slaughtered… And then once more in slow motion. We then discover that it’s a home movie shot by Benny and that continually watching the pig’s death is the only thing that moves him to emotional response. He is as vacuous and unreceptive to his parent’s mundane requests as to horrific news stories from the world around him.

-> The Piano Teacher

The Piano Teacher

A twisted tale of repressed desire, psychosexual drama La Pianiste examines the deeply rooted issues of middle-aged piano tutor Erika, who regularly indulges in sexual self-mutilation, voyeurism and various other fetishes. Simultaneously rejecting and obsessing over the advances of a young male student named Walter, the film climaxes when she finally acquiesces and lets him beat and rape her, only to find that the reality of her desires does not match her conception of them. Strangely, in such a difficult watch, the toughest scene is the relatively tame close. Asked to fill in for a female companion of Walter (whom she jealously sabotaged) at a prestigious concert, Erika stabs herself in the shoulder and leaves. Though her injury doesn’t appear that severe, Haneke gravely implies that further self-harm will ensue.

-> Caché

Caché (Hidden)

As close to a whodunit thriller as Haneke is ever likely to come, Hidden again concerns the torture of a comfortable family, albeit in a much less overt way. When surveillance footage of their home starts arriving at the door, paranoia begins to cut deep due to the simple knowledge that someone is watching. Subsequent tapes provide clues about the sender, who may or may not be involved in a dark secret from the father’s past and this deliberate ambiguity leaves us uncertain as to whom to point the blame. A dream sequence from his childhood creates a sense of nightmarish uncertainty, as he both implicates a former friend in the crime, and is overcome by guilt for a betrayal which is hinted at later. One of only two fleeting moments of intense violence in a film with overbearing violent undertones, the most striking element of the chicken decapitation is its suddenness; Haneke throws us in the deep end and refuses to give any foreshadowing or reasoning behind it. Mirroring a later moment of sudden and inexplicable violence, the two scenes merge and leave us with the disconcerting feeling that we ourselves are part of the violent act.